This is an interview conducted by the journalist Sherry Howard, the article is published on https://myauctionfinds.com/2022/05/09/reba-dickerson-hill-masters-art-and-life/.

I’ve always liked the sound of Reba Dickerson-Hill’s name. It has a melodious rhythm, like the words to a poem, emoting a power in their connectedness that would be lost if there were only two.

I learned of her not long after I began touring auction houses. At auction some years ago, I bought my first artwork by her – a lovely pen-and-ink painting of a coastal marsh with a watercolor sky dipped in blues and a terrain in tree-bark browns. It was titled “Duck Blind,” and it had been exhibited at what was then called the Woodmere Art Gallery in Philadelphia. I was curious about her as an artist, but I could find very little information about her.

Last year, I met her oldest son Harold W. Hill Jr. at an event at the now-named Woodmere Art Museum. He has spent the past couple years trying to pull her out of the shadows. He is digitizing her paintings, exhibition catalogs, notebooks, diaries and other documents. Harold has built a website of her artwork and is selling some of the pieces.

He wants the world to know the artist who painted at her enamel-and-metal kitchen table as he and his siblings played around her feet, who spent her nights and summers creating artworks in her third-floor studio, and who was educated as a schoolteacher but self-taught as an artist.

“She said that there were three things she wanted: to be a famous artist, have a family and have three kids,” says Harold, 79, her middle child. “She knew what she wanted. She wanted to be the artist, No. 1, be married and have three kids, and she did all of that.”

Dickerson-Hill accomplished her goals at a time when women weren’t necessarily encouraged to work outside the home but inside it as caretakers. The Philadelphia Tribune was so fascinated with her ability to do-it-all that the newspaper published an article in 1960 under the headline: “Mother successfully combines three careers.”

She was among a handful of Black female artists in Philadelphia during the first half of the 20th century. Black artists – women even more than the men – were shunned by most white art galleries and museums, which refused to exhibit their works. She participated in shows at the Pyramid Club, a social organization founded for Black men, that held art exhibits in its building in North Philadelphia starting in 1937. The club accepted Black and white female artists and white men as exhibitors.

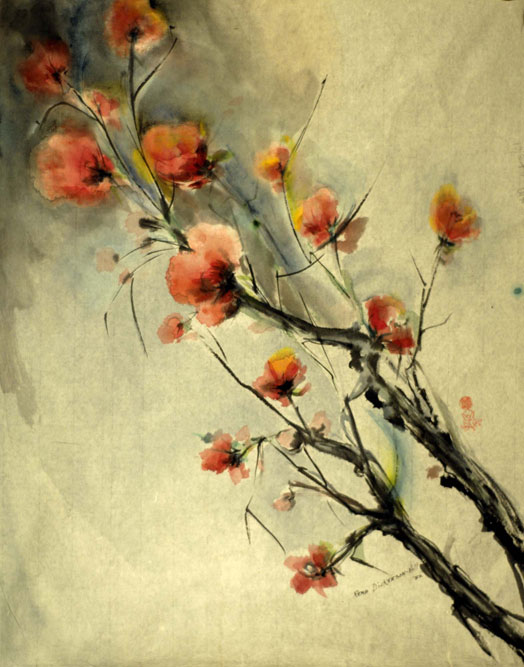

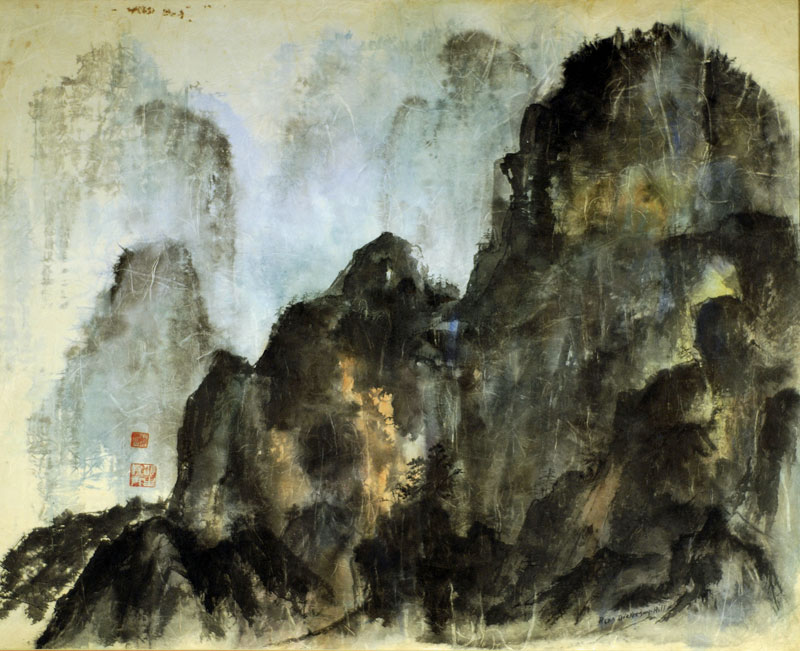

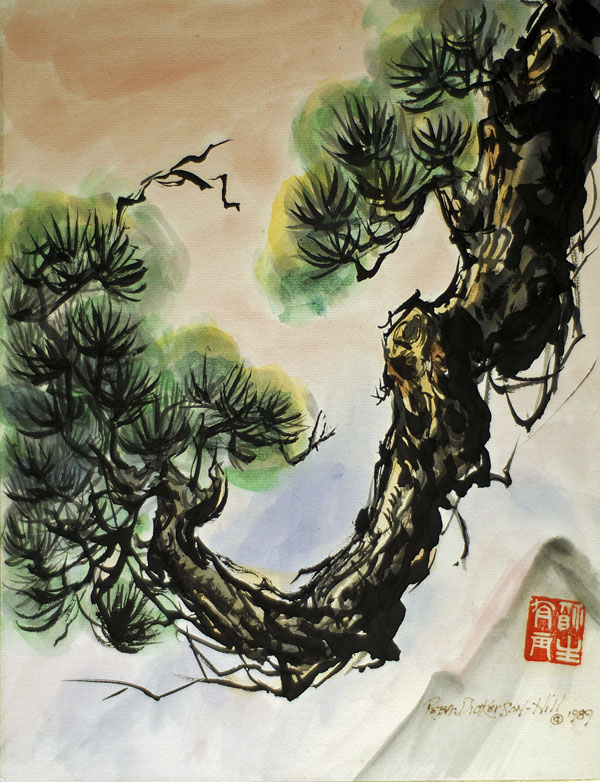

Dickerson-Hill was a nationally and internationally known artist who mastered sumi-e, a Japanese technique of ink-and-brush painting that required mastery of the mind just as much as the brush. A watercolorist, she applied that medium to some of her sumi-e artworks. She also produced oils, collages, mixed media and acrylics, pen and ink drawings, and prints, including linocuts, woodcuts and intaglio, says Harold. At one point, she made copper Jewelry in a kiln in her basement.

“She was fearless,” Harold says. “She would just go ahead and try it out and build her skills by doing it.”

Dickerson-Hill became an artist through determination and curiosity – guided first by her father and then an elementary school principal. She was born in West Philadelphia in 1918 to Evan Thomas Dickerson, a 33rd Degree Mason, and Reba Henrietta Tyree Dickerson. Her mother was of Leni-Lenape heritage, she told a writer for the Mount Airy Express in 1987. One of six children, she was called Little Reba because she was the short one in a family that towered over her, says Harold.

She was drawing at age 4 (most times, on the walls of her family’s home, one newspaper interviewer wrote). Her father noticed his daughter’s prowess, considered her a prodigy and fed her talent. He gave her a book of beautiful artwork that “was part of her motivation and stimulation,” says Harold.

As a youth, she sketched along the Benjamin Franklin Parkway in Philadelphia, particularly near the fountain in Logan Square, she said in a 1992 Philadelphia Daily News article about the city’s public art. Among her favorite pieces of public art were the maidens in the fountain.

Dickerson-Hill attended Overbrook High School at the same time as the future helicopter pioneer Frank Piasecki. She enrolled at Cheyney State Teachers College (now Cheyney University), graduating with a bachelor’s degree in education. In the late 1930s, she received a scholarship administered through the college from the Richard Humphreys Foundation.

A 1940 Baltimore Afro-American newspaper article about Cheyney graduates noted that “Miss Reba T. Dickerson,” an artist, planned to make it her career. She taught elementary grades in the Philadelphia public schools starting in 1949 and spent some time in the 1960s teaching fine arts at Cheyney. Around the mid-1960s, she gave up teaching to become a full-time artist.

She married Harold W. Hill in 1940 and soon began her family: first, daughter Reba, then Harold Jr., followed by son Allan. She had met all her criteria for success, and spent the rest of her life doing what she loved best – painting, experimenting and learning.

While their father was in the Army at Fort Dix, NJ, Harold says, the family lived in a public housing development in North Philadelphia where families embraced each other’s children. That’s where his mother painted at the kitchen table. Then the family moved to West Philadelphia. Around 1950, they moved to the Germantown section of Northwest Philadelphia into a home where Harold Sr. built her a studio on the third floor.

It was her “sanctum santorum,” Harold says. She told a newspaper writer that she spent up to six hours a day there (sometimes heading upstairs after dinner, Harold recalls). “When I am ‘on,’ I paint all day. … When I have my paint brushes, my music, I am happiest,” she told the Mount Airy Express newspaper writer. Bach was among her favorites, she told another newspaper writer.

Despite a razor-sharp focus on her art, she was always available for her children. “She would give you her attention, whatever it was,” says Harold, and then “her focus would go right back to what she was doing, never missed a beat. She was dedicated and as serious as you could possibly get about her work.”

Dickerson-Hill did not have an art degree. She learned painting techniques by research, reading books, looking at the works of other artists and studying with some of the best. In 1964 she was taught printing by painter/printmaker/illustrator Jerome Kaplan, according to a 1969 Tribune article. Her other teachers were Paul Keene for painting, Marvin Bileck for calligraphy and Ramon Fina for kinesthetic Chinese watercolor technique, according to the article. Fina exhibited at the Pyramid Club in 1947.

In the mid-1940s, she took private lessons with Claude Clark who, like artist Benjamin Britt, became a good friend. In the 1950s, both she and Britt were members of Les Beau Arts, an organization of Black people talented in arts, music and literature. Dickerson-Hill also studied at the Barnes Foundation around 1947.

In 1959, she attended a presentation at the Plastic Club conducted by Fina, an expert in Chinese brush painting. Harold has a pamphlet that he signed. In an interview in the Chestnut Hill Local, Dickerson-Hill told a story about a friend encouraging her to show her pen-and-ink drawings to Fina at some point, but she was too shy. So the friend took them to him, he was impressed, and Dickerson-Hill began studying with him. Fina lived in Philadelphia in the 1950s.

Her progression in pen and ink went from the “western watercolor technique and her fascination with the Chines kinesthetic style to the Japanese Zen which led her to sumi-e,” says Harold. Her 1994 obituary in the Philadelphia Inquirer stated that she learned of the sumi-e process from Fina while studying at the Barnes.

Sumi-e is a Japanese word for “Black ink painting” according to the website of the Sumi-e Society of America. Developed in ancient China and migrating to Japan, it emphasizes the stroke of the pen on paper, and is described as “writing a painting” or “painting a poem.” Its tools are ink stick, ink stone, brush and paper. The brushes are handmade of animal hair.

The preparation process for sumi-e is ritualistic and starts before pen touches paper. Dickerson-Hill told an interviewer for the Mount Airy Express in 1992 that she meditates first – not in a yoga pose – but by calming herself and clearing her mind. Then she prepares the ink in a traditional process with the proper tools. “The Japanese, their love of beauty, is so interpreted,” she said. “There’s a unity between the mind, body and soul. The chi, your inner soul, has to be in your brush stroke.”

The practice is very disciplined, precise and unforgiving. It requires patience, practice and sometimes repetition to master it. Once applied, lines cannot be altered. (A 1951 article about Fina mentioned that when he worked, he produced 50 small paintings daily in the traditional Chinese brush technique and chose the best one of them).

“Light and shade backgrounds are not used in sumi-e,” Dickerson-Hill told the Mount Airy Express writer in 1987. “Rather, the white untouched area of the paper serve as background and give the finished painting a look of elegance and refinement. … You even have to breathe a certain way. From the very beginning I felt at home with this expression of art. There is no rhyme or reason why. I’ve always felt this connection to the Orient, both physical and spiritual.”

Dickerson-Hill went to Japan for the first time in 1986. She visited Tokyo, Kyoto and Nara, according to a 1987 article in the Germantown Courier. She later participated in a two-week workshop on sumi-e in Exeter, England, conducted by renowned Japanese master Shozo Sato. She also visited Austria with the Sumi-e Society of America, according to Harold.

“Prof. Sato told me, when he saw my paintings, that I had a true understanding of the Zen approach to art, which is what sumi-e is all about,” she said. “It’s more than painting. It’s really a doctrine, a philosophy. It’s more than visual, it’s a belief.”

Dickerson-Hill used signature stamps on some of her sumi-e paintings. “My stamps have meanings behind them,” she told an interviewer at an October Gallery Art Expo in 1988. “They were specially done for me. One is my name in Japanese and the other means woman who loves art and beauty.”

She never totally gave up watercolor, Harold says, but instead incorporated it into her pen-and-ink drawings. She also continued to paint oils and mixed media. “She never moved away from anything, she just added more” to her repertoire, he says.

Dickerson-Hill’s paintings can be found in museums in England and Austria, according to Harold. She won several national awards, including two from the Sumi-e Society of America, of which she was a board member and life member.

She exhibited in solo and group shows at places ranging from private homes to galleries to the YWCA and YMCA to colleges to churches. In 1946, when she was around 28 years old, she was part of a group show sponsored by the Henry O. Tanner Memorial Fund, which was created to showcase young Black artists. The exhibited works were presented to community organizations. Her entry “Still Life” went to St. Christopher’s Hospital for Children and “Study No. 2” to the Crime Prevention Association.

In 1969, she was featured in a show of 100 of the country’s foremost Black artists mounted by the Philadelphia School District and the Museum of the Philadelphia Civic Center.

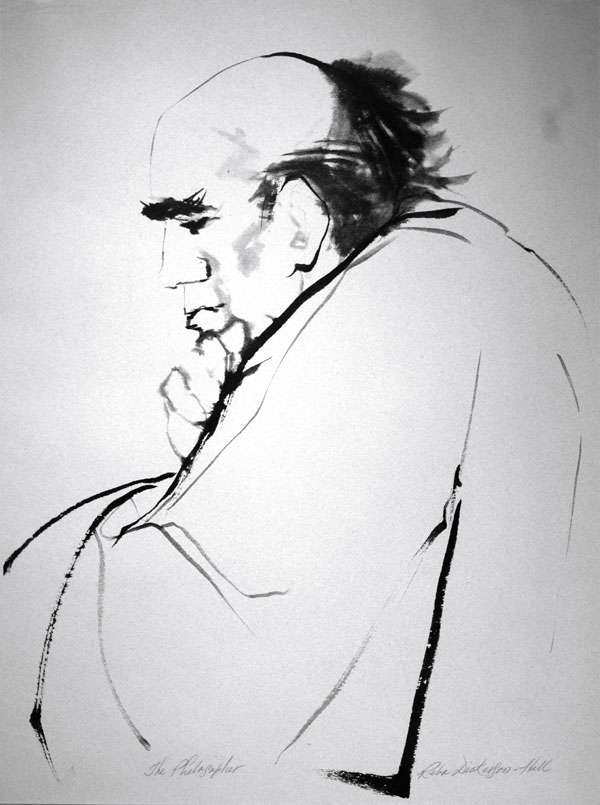

What is perhaps Dickerson-Hill’s most recognizable print is “The Philosopher,” which has come up at auction several times. She is a listed artist: she has exhibited widely, can be found in art books and catalogs, and has a record of sales. In 2021, she was represented in a re-creation of Percy Rick’s exhibition “Afro-American Images 1971” at the Delaware Art Museum. In 2015, she was part of the Woodmere Art Museum’s exhibition “We Speak: Black Artists in Philadelphia, 1920s-1970s.”

Dickerson-Hill was African American, but her choice of subjects did not identify her as a “Black” artist. She primarily painted landscapes and faces or portraits, which were artistically neutral. She felt that many people were not as enthused with her work because of it, Harold says, adding that she saw herself as an artist, period. “As an American,” Harold explains. “Reba Dickerson-Hill, Artist. That was on her business card. And I think that’s legit, and it spoke to her view of the world.”

He says she was always interested in the plight of African Americans and African peoples. A few years before she died in 1994, she produced images of African peoples on tiles.

Harold tells the story of an experience with his mother that demonstrated her artist’s eye for details. The two were visiting the Philadelphia Museum of Art, walking along and chatting when she stopped and stood quietly. Then she said, “Look at all those greens.” He looked and all he saw was one color of green in the trees around them. He realized that she saw numerous shades of the color.

“That was a significant moment in my young adult life, when I actually got to see something from her point of view,” he says.